Penang's Cina Wayang (Chinese opera) – for gods and ghosts

Growing up in Ayer Itam in the 1970s was like being part of a celebration that never truly ended. The wet market was the heart of our lives, a place where food was not only sold but also shared, improvised and made personal. We carried our own tiffin carriers, sometimes even our own eggs, to hand over to the char koay kak lady or to Pak Dollah, the mee goreng man. They accepted them without question, as if it had always been the way things were done. Ah Heng, the rojak man, set up his cart just outside my house. I can still picture him skewering green mango halves with a lidi, topping them in thick rojak sauce and crushed peanuts—a truly scrumptious snack. His bangkwang slices, prepared in the same way, were another favourite of mine, cool and crunchy against the richness of the rojak sauce. In time, Ah Heng moved from rojak to koay teow th'ng. I thought I would miss the old flavours, but his bowls of noodles soon became their own kind of comfort. Minced pork, tender slices of meat, liver and fish balls where everything came together in a broth that warmed you from the inside out. And always, there was the finishing touch of bak yu phok (fried lard) and spring onions.

In those days, everyone knew everyone, and gossip travelled faster than a speeding bullet. By the time I reached home, my mother already had a detailed report of my mischief, complete with commentary from half the neighbourhood.

Nowadays, Chinese opera shows are few and far between, appearing mostly during the Hungry Ghost Festival or on the birthday of a deity. But in the 1970s and 1980s, they were a regular spectacle and the carnival atmosphere was electric. Food stalls and petty traders filled the grounds, transforming the place into a paradise for children. There was the thrill of “tikam,” where a small payment bought a ticket and the chance of a mystery prize. There was the delight of “ice cream potong", sandwiched neatly between two wafer biscuits, or the excitement of spinning a wheel in hopes of winning a water pistol. All the while, the irresistible aroma of freshly grilled roti bak kwa and cuttlefish drifted through the night air, teasing the senses and tantalising your taste buds.

The crowds were huge, with families bringing their own stools to secure the best view of the classic Teochew opera tales. The drama on stage often rivalled the commotion below, as people jostled for space at the food stalls while being entertained by the soaring voices and clashing cymbals of the performance. It was a feast for the senses—sights, sounds, and flavours tumbling together in a joyful chaos that etched itself into the memory of anyone fortunate enough to be there.

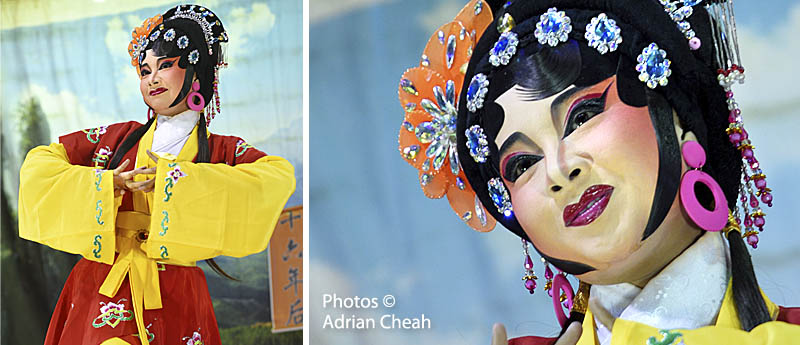

My brothers, sisters, and I needed only to cross the road in front of our house and slip through a narrow alley to reach the open space where the performances came alive. I was mesmerised by the splendour of the costumes, embroidered with dragons, phoenixes and other auspicious creatures, paired with glittering headdresses that caught the light. The music filled the night air, rising and falling with a drama all its own. We sat spellbound, glued to our seats, as the performers whisked us away into a whirlwind of murder, sword fights and romance. Each of them, dolled up with heavy make-up, poured heart and soul into every gesture and every line.

Every change of scenery was achieved through a simple pulley system that unveiled floor-to-ceiling hand-painted backdrops, transforming the stage in a heartbeat from a blood-soaked battlefield to a serene courtyard. To us, it felt like witnessing a soap opera brought to life, where the stakes were grand and the characters strode across the stage larger than life itself.

A small band of musicians, tucked at the wings of the makeshift stage, carried the performance with its stirring soundtrack. The gaohu, erhu, yehu, pipa, dizi, gongs and cymbals create the unmistakable voice of Chinese opera, at once haunting and rousing. The stage itself glowed like a beacon against the night, illuminated by fluorescent tubes and spotlights, casting an enchanting glow over the unfolding drama.

Ironically, I fell in love with Chinese opera even though I could not understand a single word spoken on stage. I pieced together each story by watching the performers’ faces and gestures, learning to read the drama through movement and expression alone. The male characters, with their flowing beards, rumbled in deep, growling tones, while the female characters sang in high, lilting voices that seemed to pierce the heavens. Some wore long white silk extensions on their sleeves, which they flung about to magnify their emotions. In moments of despair, the heroine would dramatically sweep her arm skyward before collapsing to the ground, overcome with anguish.

At home, I would tie my father’s white handkerchiefs to my wrists and imitate the sweeping gestures I had seen on stage. To me, it was poetry in motion, a way of keeping the magic alive. My parents, however, thought otherwise. They considered it silly and would brandish the cane, swiftly putting an end to my operatic aspirations.

When I revisited Chinese opera in 2019, I went armed with a camera to capture its world on the open grounds near Universiti Sains Malaysia along Jalan Bukit Gambir. To my astonishment, apart from three other photographers, there was only a single audience member, a solitary elderly man. Just one!

It was a far cry from the old days, when entire communities would gather, gossip and bond over the thrill of a live performance. Today, it seems people prefer the comfort of their homes, wrapped up in Netflix marathons rather than the spectacle of opera under the stars. Thank goodness the gods and ghosts were still present to bear witness to a performance worthy of a full house, even if the living had chosen to turn their backs.

Arriving early, I was able to witness the performers’ dramatic transformation into either enchanting heroines or menacing villains. Layer by layer, elaborate designs were painted onto their faces, each brushstroke shaping a character’s identity, role and fate. The colours spoke their own language—red conveyed loyalty and courage, black stood for strength, while white or yellow suggested deceit, often marking the villain. Faces adorned in gold or silver carried an air of mystery to the mix.

In addition to colour, the painted lines carried their own meanings. A face might be entirely white or marked only around the nose; the larger the white area, the more sinister the character. Watching the make-up take shape was an experience in itself. The precision and patience were extraordinary, with even tiny patches of real hair painstakingly affixed to create natural-looking fringes and sideburns. By the time the transformation was complete, the result was nothing short of resplendent.

This opera troupe had come from Thailand and its members proved to be captivating subjects for photography. They lived in modest tents pitched within the temple grounds, never far from the stage where they performed. What struck me most was their warmth and the unshakable bond they shared, a quiet strength that spoke of years spent together in the service of their art. Watching them, I felt a deep admiration for their devotion to a tradition that is slowly fading, and for the tireless commitment with which they kept it alive.

I felt privileged to witness the performance, yet it was difficult not to feel a twinge of disappointment at how little attention this traditional art form now receives from the local community. It is a pity, for with all the splendour that surrounds Chinese festivals in Penang, one would expect crowds to gather in support of these performers.

Still, I choose to hold on to hope. With effort and awareness, there is every chance of a revival. We need to rekindle our appreciation for these timeless treasures and ensure that they continue to shine for generations to come.

-------------------------------------

Written and photographed by Adrian Cheah

© All rights reserved

16 August 2019