Lifting hope in Penang at Wat Buppharam Buddhist Temple

Wat Buppharam may not appear on every traveller’s must-see list in Penang, but those who step into its tranquil embrace are often rewarded with sacred and unexpected discoveries. Can a silent statue whisper the truth of your wishes? Within its shrine hall rests a humble, one-foot-tall figure known as the “Lifting Buddha”, a sacred icon believed to be able to reveal just that!

A Sacred Honour for a Devoted Life

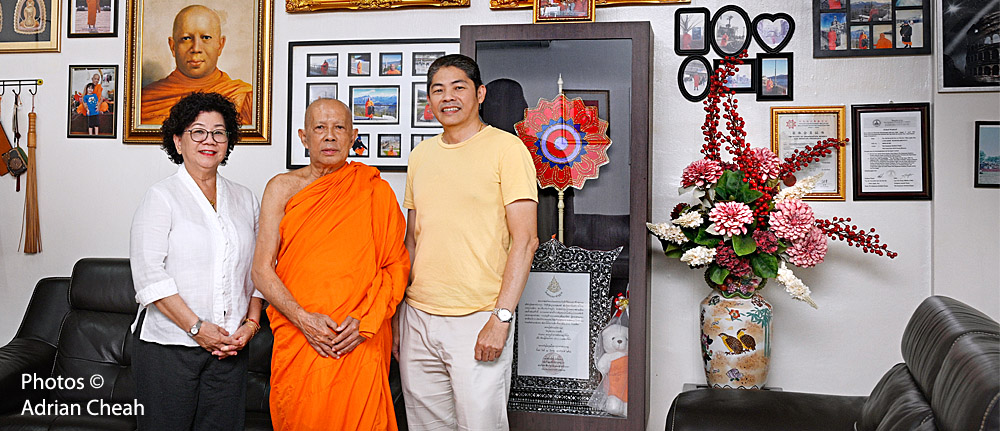

On 2 July 2025, I visited Wat Buppharam for the first time. It was a special celebration to honour the temple’s Chief Monk who had received a newly conferred ecclesiastical peerage from the King of Thailand.

The certificate and ceremonial fan had been presented earlier in Thailand to Venerable Than Archan Nui. Bearing the golden royal seal and written in Thai script, the certificate carries the official decree from His Majesty King Maha Vajiralongkorn Bodindradebayavarangkun. The title conferred was Phra Khru Phothithamwat (Nui), appointing him to Wat Buppharam, Malaysia, as Phra Khru Abbot of a public temple, second class (a rank equivalent to Assistant Abbot of a Royal Monastery, second class). The title was issued by Somdet Phra Ariyawongwongkhatayan, the Supreme Patriarch of Thailand and President of the Sangha Supreme Council.

The honour recognises the monk’s long-standing service and commitment to the Buddhist community he serves. Though a Second Class distinction, it carries significant respect and reflects his contributions to the monastic order. The certificate was set in a black-and-white frame with mother-of-pearl inlay. The fan, shaped like a sixteen-pointed star, is trimmed with thick gold thread and affixed to a white handle, mounted on a matching stand. This serves as a ceremonial symbol of his role and the Thai monarchy’s spiritual acknowledgement.

The celebration culminated with prayers and a sumptuous luncheon prepared by devotees. It was a joyful moment not just for the Chief Monk, but for the entire Wat Buppharam community.

Some might see the giving of titles and honours to monks as contrary to Buddhist ideals of renunciation. I choose to view it through a different lens. These honours are not meant to elevate the individual or ego, but to affirm the responsibilities that come with the title. A monk is expected to accept it with humility and detachment, seeing it as a continuation of duty, not personal achievement. The fan and certificate, then, are not symbols of privilege, but of the enduring service to the Buddhist faith. As with many things in life, the intention matters most—especially in what we tell ourselves, even when no one can listen in.

The Lifting Buddha

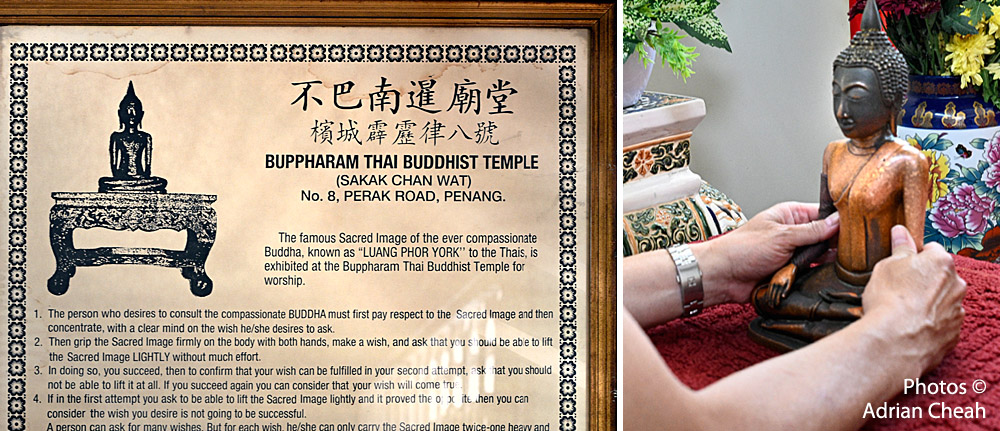

Within a small annexed room on the right of the main temple resides its most curious treasure: about a foot-high bronze Buddha statue (also known as Luang Phor York to the Thais). Its fame stems from the ritual of the Lifting Buddha, where one clutches and lifts the statue with the intent to see if one’s wish will come true. If one manages to lift it on the first attempt, it signals a promising outcome. Paradoxically, the second attempt, though unsuccessful, confirms that fate favours the desire.

I no longer pray the way I once did. After more than half a century on this earth, I have stopped asking for outcomes, for safety, for healing, for the deliverance of those I have loved and lost. I have learnt that life moves in its own rhythm, untouched by how many prayers I storm heaven with. These days, I go to church simply to be, to sit in quiet gratitude and breathe love. No requests, no lists, just presence. A still moment to send love, through thought and heart, to those who matter most.

Encouraged, I reached out and lifted the sacred Buddha. The statue, unexpectedly heavy for its size, but with some effort rose in my hands on the very first attempt. I stopped there. I did not need further confirmation. And what did a Roman Catholic like me wish for in that precise moment? Only this: that I might have the insight to write a meaningful, honest story about this very intriguing temple.

I do not claim to know what draws devotees to this ritual. Perhaps it is not just about seeking confirmation, but a longing for clarity, a pause amid life’s noise and unpredictability. To ask whether a wish will come true may be less about the outcome and more about reassurance. A simple gesture, a subtle sign, that it is all right to hope.

As Søren Kierkegaard (the father of existentialism) wrote in his personal journal, “Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards". And in that forward motion, we often yearn for something to steady us, an anchor in the unseen. Faith, ritual, or even a fleeting moment of presence can offer that kind of grounding. The ritual of lifting the Buddha becomes less about prediction and more about permission: a gentle nudge to believe again and to move forward with sincerity.

According to a sign on the temple wall, the original Buddha statue is believed to be over a thousand years old, said to have come from a monastery in northeast Thailand. Archan Nui believes it was brought to Wat Buppharam by the temple’s second Chief Monk. Over time, the sacred statue was stolen, a shocking act that left many stunned. Miraculously, it was returned, only to vanish again. This time, it never came back. Archan Nui then commissioned a replacement from Bangkok, cast in solid brass. The statue now housed in the temple is this second Buddha.

Humble Beginnings

Wat Buppharam, located at No. 8, Perak Road in Penang, was founded by the Thai monk Phothan Srikheaw. Its name, Buppharam (บุปผาราม), comes from Pali (and ultimately Sanskrit) roots rendered in Thai; buppha meaning “flower” and aram meaning “temple”. Thus, it translates to “Temple of Flowers”.

While the exact founding date remains uncertain, it is generally believed the temple existed by the 1930s. "Glimpses of Penang’s Past", a compilation of articles from JSBRAS and JMBRAS, notes that Wat Buppharam stood next to another Thai temple, Wat Sawan Arun, and was once surrounded by paddy fields. In Hokkien, it was then locally known as “Sah Kak Chan”, meaning “three-cornered paddy land”.

According to a Thai manuscript written by Phra Daeng, the temple’s founder, Venerable Phra Sri Keow Suvanno was from Songkhla Province in Southern Thailand. A group of devotees donated about 10 rai (four acres) of land for the temple's construction. Early trustees included Madam Kim Heoh, Madam Kim Liew, and Madam Siew Ean, all local Chinese devotees. Monks’ quarters, a kitchen and a shrine hall soon followed. Venerable Phra Sri Keow served as abbot until his passing in 1942.

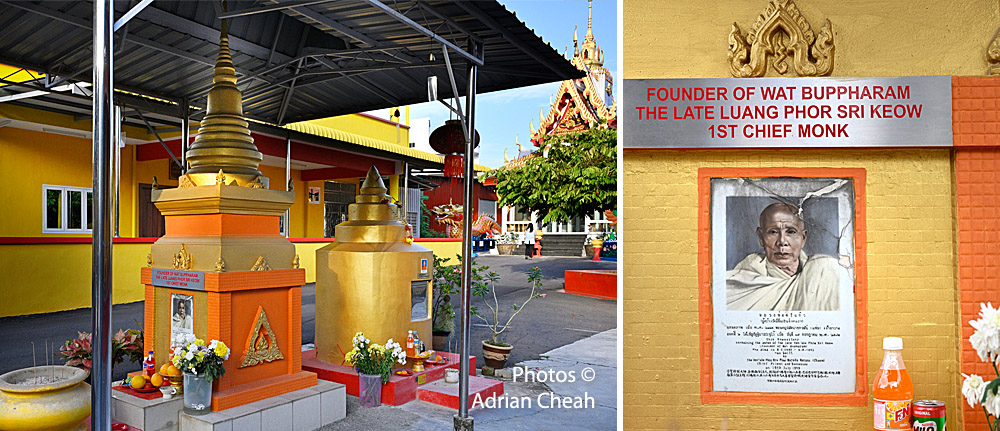

The founder Luang Phor See Keow’s final resting place at Wat Buppharam, Penang.

The temple flourished with the guidance of a lay committee and a panel of Thai ecclesiastical advisers: Venerable Phra Khru Paled Wieng, Phra Khru Mongkolpisarn, Phra Khru Sangharaks, Phra Khru Sophana Sangklakarn, Phra Khru Patihanathammakhod and Phra Khru Suphacharapratong.

Remarkably, during the Japanese Occupation, the temple was left untouched with only Phra Keow remaining. After the war, it narrowly avoided being lost to Chinese Buddhist management, a fate that befell neighbouring Wat Sawan Arun. This was thanks to the timely intervention of the Thai Consul, the Ecclesiastical Advisers, and two officials, Messrs Ariyee Howe and CH Hanson.

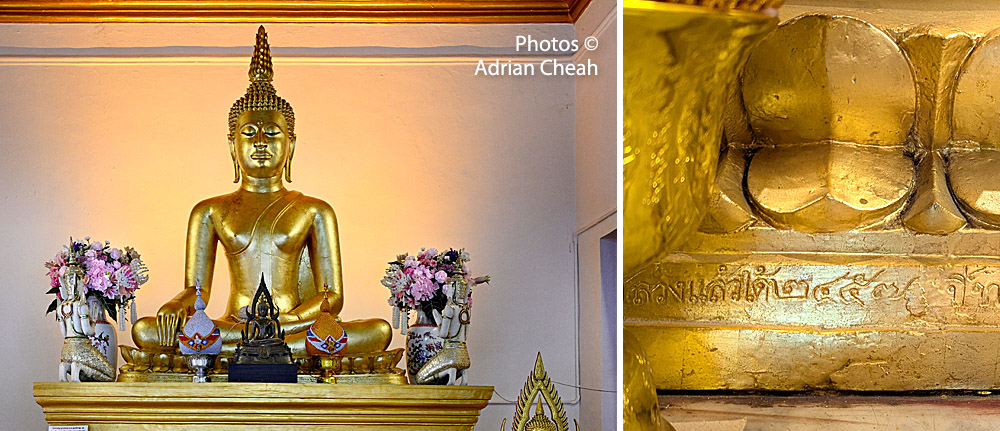

Although much of the temple’s early history points to the 1930s, I believe its roots stretch further back. An inscription at the base of the main Buddha statue dates it to B.E. 2457 (1914), suggesting that the temple’s founding predates the statue which was likely commissioned for an already-established temple. This would place Wat Buppharam at over 110 years old.

The Temple Today

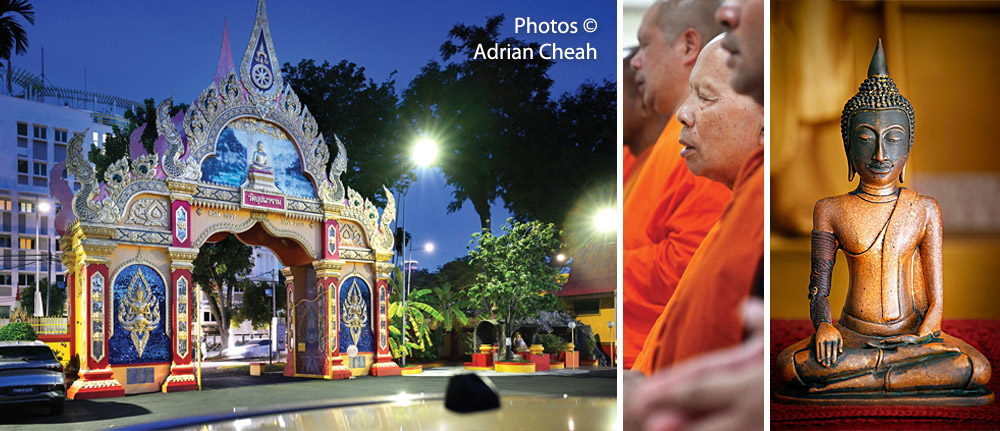

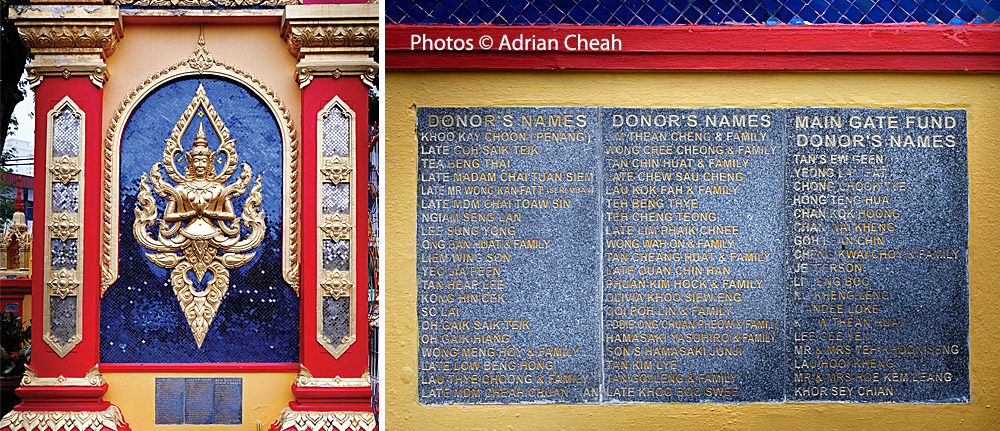

More than a century since its humble beginnings, Wat Buppharam has grown into the vibrant sanctuary it is today, thanks to the generosity of its devotees. One of the first sights to greet visitors is the majestic gateway arch, a striking landmark that welcomes visitors to the temple.

The construction of the gateway arch began in 1997 and spanned nearly three years, with skilled artisans from Thailand ensuring that every detail was executed with precision and reverence.

A granite plaque mounted on the wall bears the names of the donors, a lasting tribute to those who helped bring the ornate archway to life.

As visitors explore the ubosot, they will find themselves immersed in the harmonious blend of Thai architecture and spiritual heritage that defines Wat Buppharam.

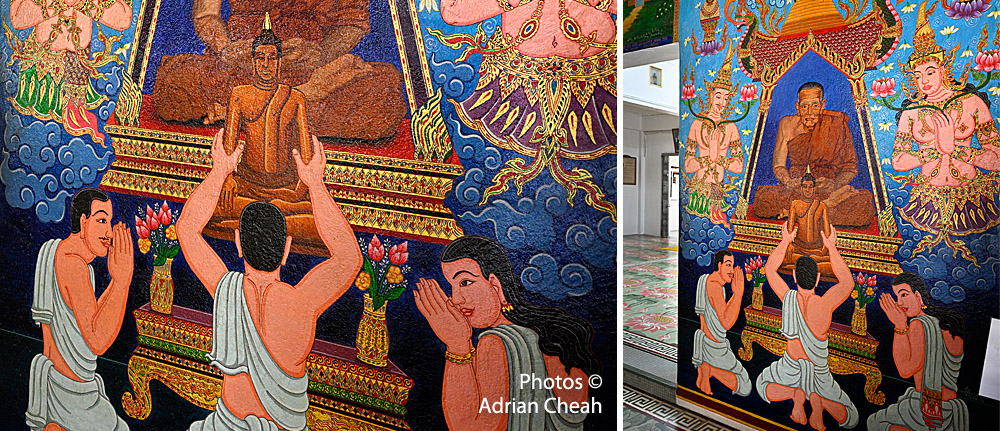

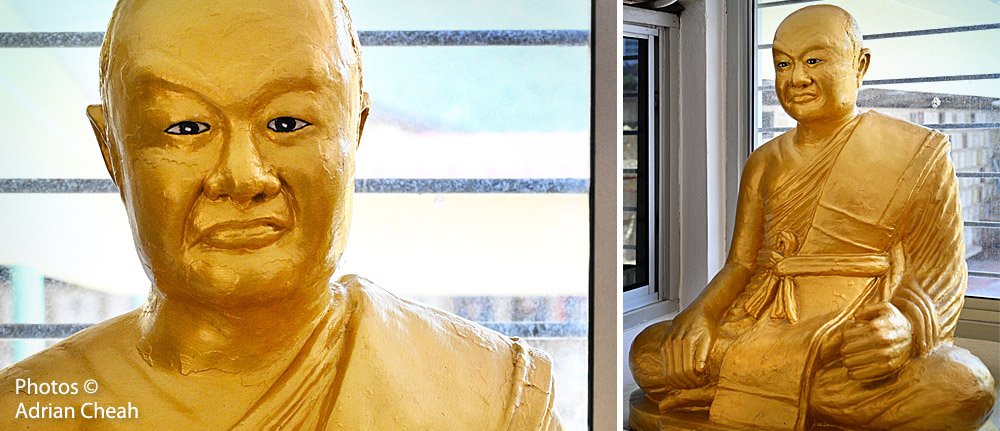

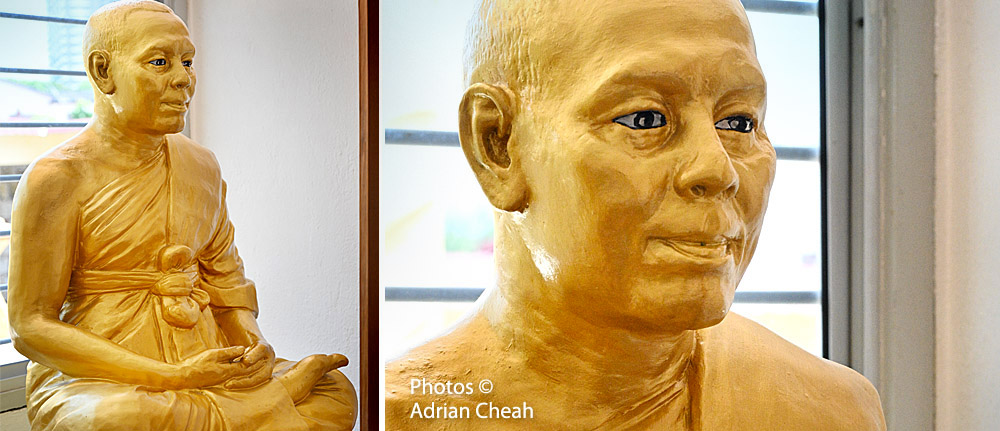

Let us begin by paying homage to the Chief Monks who have guided Wat Buppharam on its spiritual journey. The temple’s founding father is commemorated with a life-like golden statue, accompanied by those of the second, third, and fourth Chief Monks. These revered figures are enshrined in two annex rooms flanking the main hall, one to the right and the other to the left.

The first Chief Monk, Luang Phor See Keow.

The second Chief Monk, Luang Phor Cham.

The third Chief Monk, Luang Phor Daeng.

The fourth Chief Monk, Luang Phor Chooi.

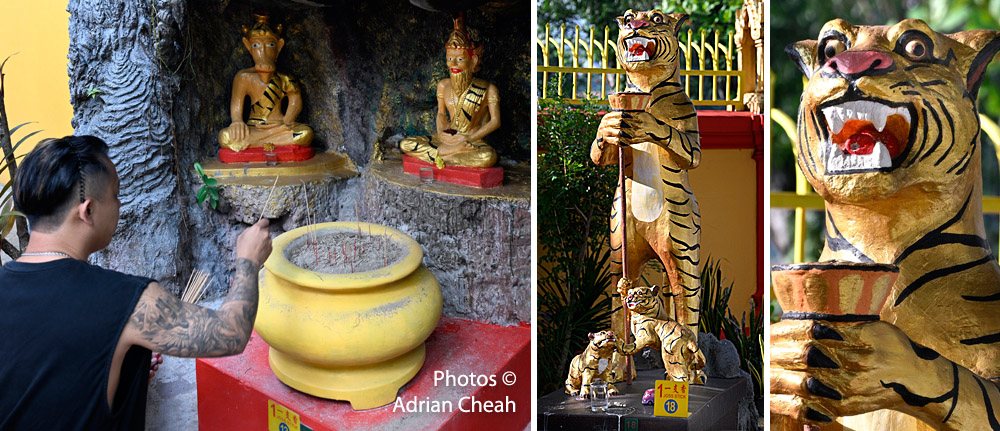

Beyond the main shrine and monk memorials, the temple grounds are dotted with statues representing a rich tapestry of spiritual traditions. These include revered Hindu deities, Buddhist figures, and symbolic icons placed in quiet corners and garden spaces.

A golden statue of the Four-Faced Buddha, seated in serene majesty. Known in Thai as Phra Phrom, this revered deity is the local representation of the Hindu god Brahma. Each face symbolises a divine virtue—loving-kindness, compassion, joy, and equanimity—offering blessings in all directions.

On the right at the entrance of the temple a statue of Lord Ganesha is portrayed in a seated pose, the Hindu deity with an elephant head and four arms. Revered as the remover of obstacles and the god of good fortune, prosperity, and wisdom, he bears the red "Om" symbol on one palm. Representing the essence of the universe and ultimate reality, Om is believed to be the primordial sound from which all creation emerged. It is often chanted in meditation and prayer.

On the left at the entrance of the temple is Lord Vishnu, the preserver and protector in Hinduism. Depicted with blue skin and four arms, he holds a conch shell (creation), a discus (destruction), a mace (time), and a lotus flower (purity). These sacred symbols reflect his divine role in maintaining balance and cosmic order.

Despite the diversity of spiritual iconography across the temple grounds, the monks of Wat Buppharam remain firmly rooted in Theravāda Buddhist teachings, rituals, and practices. The presence of non-Buddhist statues, from Mahāyāna bodhisattvas to Hindu deities, often stems not from temple doctrine but from circumstance. One ongoing dilemma is the growing number of religious statues left behind by people who no longer wish to keep them, sometimes simply abandoned at the temple grounds. When asked about this, Archan Nui sighed, “What to do… we just accept them.” It is an act of compassion, not endorsement.

Beyond the monks’ hostel stands a majestic rice pagoda, shaped like a mondop and flanked by two huge auspicious dragons in protective stance. Devotees offer bags of rice, placing them within the pagoda as acts of merit. Depending on the volume collected, the rice is used to support the temple, distributed to those in need (old folks' homes and orphanages), or channelled to temples in flood-prone regions like Kelantan during the monsoon season.

A majestic Bodhi tree stands on the temple grounds, its origin is unknown. Yet, it would not be surprising if its lineage could be traced to the sacred Bodhi tree of Anuradhapura in Sri Lanka, believed to be a direct descendant of the original tree in Bodh Gaya, India, beneath which Siddhartha Gautama attained enlightenment. In Penang, Bodhi trees at Mahindarama Buddhist Temple and the Penang Buddhist Association are known to share this honoured heritage.

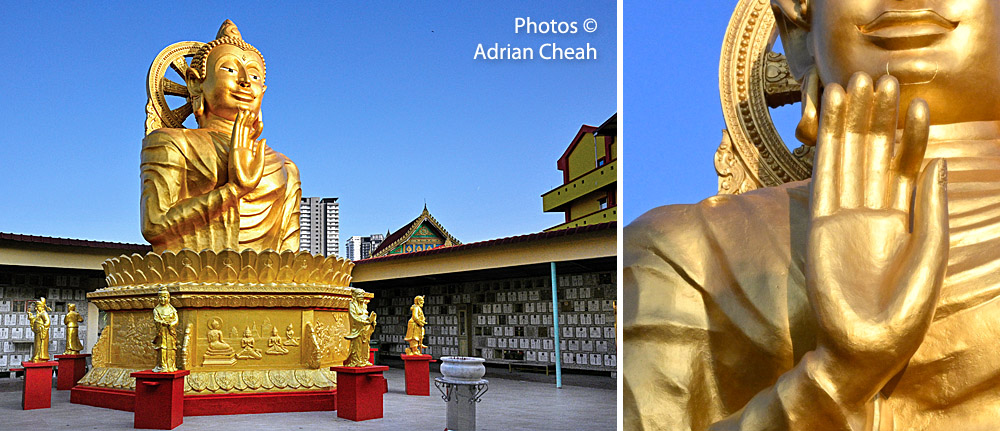

At the rear of the temple grounds stands a serene columbarium, its walls lined with niches for the ashes of the departed. At its heart, within an open-air courtyard, rises a towering golden statue of Lord Buddha, his palm extended in the abhaya mudra gesture symbolising fearlessness, protection, peace, and compassion. Encircling him are Taoist deities.

The Chief Monks of Wat Buppharam

Since its inception, Wat Buppharam has been guided by dedicated Chief Monks. The founder and first Chief Monk was Luang Phor See Keow (Venerable Phra Sri Keow), who passed away in 1942. Under the second Chief Monk, Luang Phor Cham (Phra Kru Plad Nayaka Watana), the founder’s ashes were returned and interred in the temple on 19 July 1959.

The third Chief Monk, Luang Phor Daeng (Phra Daeng Atipalo), officially received his Position Seal as abbot on 9 March 1980 at Wat Chaiyamangalaram. He was succeeded by the fourth, Luang Phor Chooi (Phra Khru Bidhikacheay Akhathammo), who continued to uphold the temple’s spiritual traditions.

The fifth Chief Monk, Phra Palad Yan Jong Khantipalo (Than Yong), was born in Kelantan in 1974 and entered monkhood in 1997. In 2000, he attained the highest level of the Dharma examination under the Thai King’s patronage, a significant scholarly achievement in the Thai Buddhist tradition. He became known for consecrating amulets, most notably the Pidta Kut, introduced in 2005. However, due to certain challenges during his tenure, his stewardship was relatively short. A few years later, the mantle of leadership passed on to the sixth Chief Monk.

The Sixth Chief Monk

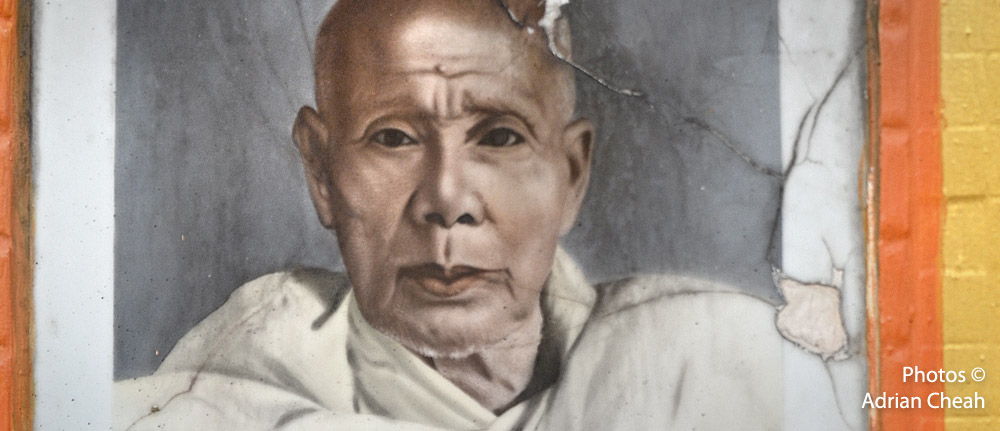

The current Chief Monk is Phra Kru Phothitummawat (Archan Nui). Born in 1946 in Kelantan, Eh Nui was the youngest of six siblings, two brothers and four sisters. His father was Nai Pha, and his mother, Nag Si, was of Thai descent. His spiritual journey began early. At just six, he attended classes at Wat Phothivihan in Tumpat, a Thai temple now known for its reclining Buddha. There, he was introduced to monastic life and received his early education in reading, writing, and Buddhist teachings—all in Thai. Though he never attended formal school, the temple shaped his formative years.

Right, a treasured photograph of Archan Nui’s mother, Nag Si, rests on the altar in his quarters. Their bond must have been profound. At her passing, he cradled her in his arms and chanted for a long while—a final act of love, honouring her journey with prayer and presence.

At twenty-two, Eh Nui chose to fully commit to monkhood and was known as Archan Nui. He apprenticed under Than Haw for over a decade at Wat Phothivihan. In his thirties, he was invited to Penang to assist at Wat Buppharam under the third Chief Monk, Luang Phor Daeng. After more than ten years of service, he went on to establish Achan Khun Nui, his own samnak (spiritual centre) at No. 2E, Scotland Road, where he continued his practice for fifteen years. There, he offered personal blessings and became known for his skill in crafting palakit talismans and amulets, attracting devotees seeking both protection and spiritual guidance.

In the early 2010s, he was nominated by Than Piang of Wat Pinbang Oon to serve as the sixth Chief Monk of Wat Buppharam. His appointment was affirmed through consensus among senior Thai monks and spiritual mentors in the region, in keeping with traditional Thai Buddhist monastic practice.

Sacred Amulets and Palakit Talismans

Archan Nui is deeply respected for his craftsmanship of sacred amulets, particularly Phra Pidta, and palakit talismans. He learned the art of crafting the sacred amulets from Than Hwa of Wat Phothivihan in Tumpat, Kelantan, and Phor Than Daeng (Than Daeng) of Wat Thong Dee Pachalam in Sungai Golok. Both of these revered monks were themselves disciples of the legendary Tok Raja (Luang Phor Kron), also known as Than Kron of Wat Uttamaram, Kelantan.

Tok Raja was one of the most venerated Thai Buddhist monks in Malaysia during the 20th century, famed for his powerful amulets and deep spiritual insight. His teachings and esoteric knowledge, passed down through generations, now live on through Archan Nui.

The creation of these amulets is a meticulous and spiritual process. Various herbs and a special mix of ingredients are carefully selected and ground into fine powders. These are then mixed with binding agents such as clay, cement, or resin and moulded into specific forms. Each piece is inscribed with yantra symbols or mantras and undergoes an extended consecration period of at least three months, during which he personally performs ritual chanting and invocations. These amulets, made with the intention of protection and devotion, are believed to carry spiritual energy, offering both safeguarding and the strengthening of personal relationships (lang ean in Hokkien). This is the only kind Archan Nui makes, as there are countless amulets for various purposes. No "black magic" is involved here.

He also mastered the art of crafting palakit, a phallic-looking talisman traditionally associated with charm and personal well-being. These are often crafted from selected woods such as keluat (Palaquium spp.), a dense, iron-rich hardwood native to Malaysia long believed to hold protective spiritual properties, and mairak (Siamese Rosewood), a dark, resilient wood prized for its durability and suitability for fine carving. Some are also available in gold and silver. Each palakit undergoes months of careful carving, the inscribing of sacred symbols, and chanting. Archan Nui learned this sacred art from Archan Thun of Nakhon Sawan, Thailand, carrying forward a lineage of spiritual craftsmanship deeply rooted in Thai Buddhist tradition.

The palakit (Thai palad khik) talisman traces its origins to ancient Indian Shiva-Linga worship, with early forms likely introduced to Southeast Asia through cultural exchanges such as the 8th-century Cham migration. It represents the phallic energy tied to fertility, protection, attraction, and life force.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, when visitors to the temple and donations declined drastically, the sales of Archan Nui’s sacred amulets and palakit provided the much-needed funds for the temple's survival. As serendipitous as it seems, his encounters with Than Hwa, Than Daeng, and Archan Thun also helped pass down a lineage of spiritual craftsmanship to the next generation. It reminds me to always carry a seeker’s heart for knowledge, for skill, and for the sound wisdom others may offer along the way.

Daily Routine

Archan Nui who turns eighty in 2025, continues to live a life of disciplined devotion. He wakes at 3:30 am and begins his day with chanting at 4:10 am, which lasts about 45 minutes. After breakfast, he carries out temple chores himself, sweeping, mopping, and tending to the grounds.

He receives visitors in the morning, offering blessings and performing the duties expected of a monk. Lunch is served at 11:30 am and marks the final meal of the day. On Wan Phra, Buddhist holy days based on the lunar calendar, special prayers are offered during lunch. These observances follow the moon’s phases, so the dates vary each month. A short rest is taken around 3:00 pm, followed by another chanting session at 5:00 pm, again lasting about 45 minutes.

After evening prayers, Archan Nui resumes light housekeeping after the temple closes its doors at 5:00 pm. During the three-month Phansa period, evening chanting secessions are held at 7:30 pm. He retires for the night around 10:00 pm.

Quiet Service to Do More

Beyond his spiritual duties, Archan Nui also oversees the temple’s management, maintenance, and finances. Wearing many hats, the weight of daily responsibilities he shoulders is immense. Yet under his steady leadership, Wat Buppharam has seen meaningful progress including the construction of new kitchen and toilet facilities, and a shaded courtyard fitted with a simple awning to offer devotees respite from the elements.

He also oversaw the building of a four-storey structure, completed on 24 May 2013. The ground floor features a spacious Kitchen Hall, ideal for hosting communal meals during festive occasions.

Above it, the Dharma Hall provides a serene and comfortable setting for chanting and meditation, while the upper levels offer lodging for outstation devotees and lay practitioners on retreat.

A separate three-storey monks’ hostel, inaugurated on 28 April 2018, further supports the temple’s growing community and activities.

Archan Nui’s life is grounded in quiet service, steady discipline, and a deep love for the temple and its people. Whatever funds come in, he sees it as a trust to care for the temple, to build what is needed, and to help those who need it most.

In 2025, his decades of unwavering dedication were recognised by the King of Thailand, who conferred upon him the ecclesiastical title Phra Kru Phothitummawat. It is a fitting honour for a life humbly and wholeheartedly given to the Buddhist path.

As for the wish I made when I lifted the sacred Lord Buddha, I will leave it to you to decide whether it has come true.

---------------------------------

Written and photographed by Adrian Cheah

© All Rights Reserved

2 July 2025

If you enjoyed this story, you may like to bookmark this site or return for future essays.

______________________

Wat Buppharam Buddhist Temple Penang

8, Jalan Perak, 10350 Penang

Open 7:30 am – 5:00 pm daily

* JSBRAS/JMBRAS: Journal of the Straits Branch / Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society.