Stitching Through Hardship: A Nyonya's War-Time Chronicle

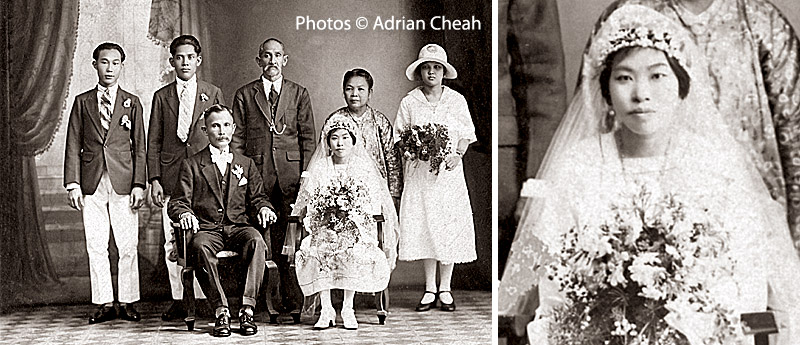

At the Church of the Assumption, nestled amidst the charming streets of George Town, the hearts of Louis Michael Martin and Emily Elizabeth Surin became forever entwined. Their love story, like a cherished melody, found its harmonious crescendo on that memorable day of 7 August 1926. Officiating their marriage was Rev. Fr. P. Lerond. The church must have looked different from what we see today as it underwent a major renovation in 1928 when two wings were added.

Emily’s baptism records which was written in Latin shows that she was adopted and baptised at the age of one year and three months. Additionally, it is worth noting that her name was listed as “Emilia” in the document. Photo © Vincent Boudville

Louis, with his French lineage and Emily, an orphan who had blossomed in the care of Light Street Convent (across from the Church of the Assumption), were a testament to love's remarkable power to transcend the boundaries of circumstance. It was not only divine providence that conspired to unite them but also the blessing of the Mother Superior of the Convent.

7 August 1926: Seated are Louis Michael Martin and Emily Surin. Marianne (in the white hat) is the groom’s niece. Second from left is Marianne’s husband, Edward. Next to him are his parents, Frederick and Adelaide Boudville.

Together, Louis 46 and Emily 30, embarked on a journey filled with hope, embracing the promise of a life shared. Their union gave birth to not only an enduring love but a family that would come to bear witness to the immense trials and tribulations of war.

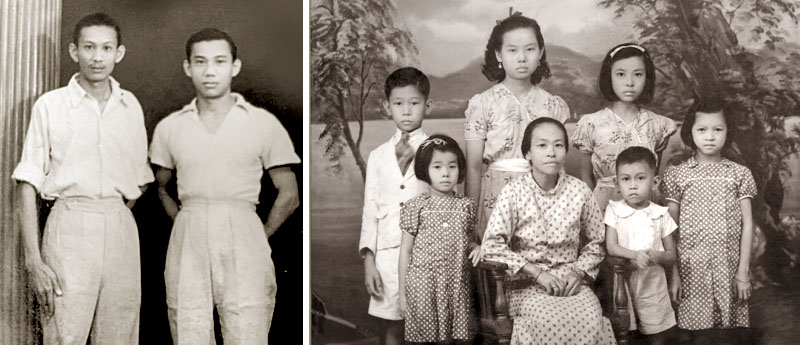

Left photo: Charles (left) and Fred.

Right photo: This family photo must have been taken a few years before WWII. Standing behind from left: Giles, Mary and Margaret. Front row from left: Patricia, Emily, Louis Jr. and Marjorie. Photos © Esther MacFarlaine

In the embrace of their love, Louis and Emily first adopted two sons, Fred and Charles, before welcoming six of their own into the world. Their children were Mary, Margaret, Giles, Marjorie, Patricia (my Mum) and Louis Jr. These names were the very heartbeat that compelled Emily to fight with all her might to keep afloat amidst the tempestuous waves of war.

Fifteen years from the day they had exchanged their vows, pledging to stand together "... till death do us part", tragedy struck. The passing of 61 year-old Louis Sr. cast a long, mournful shadow over the family. On 2 March 1941, the world lost a loving father and husband to the cruel grasp of "heart trouble". The depths of their sorrow were unfathomable, leaving a void that no amount of time could ever truly fill.

The circumstances surrounding his death remained enshrouded in mystery and heartache. Patricia, their youngest daughter, holds in her heart the belief that her father's passing had been influenced by an unsettling dark magic charm, cast upon him by their neighbour, a Malay bomoh. The day of his demise also witnessed the inexplicable death of his beloved pet tekukur (spotted dove), a poignant symbol of the family's loss. The origins of these tragedies would remain forever obscure.

Patricia noted that many years later, as age began to catch up with the bomoh, she observed an intriguing twist of fate. All of the bomoh's own children, educated in esteemed schools like St. Xavier's Institution, displayed no interest in inheriting the mantle of the dark arts and instead, chose different paths. "Shortly after the bomoh took his last breath, the very spirits that he had harnessed to do his bidding exacted a cruel toll, claiming the lives of all his children", Patricia recounted with a shudder.

As World War II began to tighten its devastating grip in the horrifying year of 1941, Louis Sr.'s passing left his beloved family navigating turbulent waters without their steadfast captain. The world, already trembling with the dark forebodings of war, grew even more tumultuous.

In 1941, Fred and Charles, who were much older (though the exact ages remained uncertain), alongside Mary (14), Margaret (13), Giles (11), Marjorie (9), Patricia (7), and little Louis Jr. (6), found themselves adrift in a world overshadowed by uncertainty. With the war came the relentless shadow of hunger and fear, agonising companions that never seemed to leave their side.

In the probated estate, it is recorded that Louis Martin Sr. provided a $400 loan to Ong Ho Tat for “payment of doctors’ bills, medicines, and other expenses incurred during his illness”. However, following Ong’s passing on 3 June 1922, it was decided that all his land would be transferred to Louis as a form of debt repayment. Photos © Vincent Boudville

In December 1941, the tumult of World War II erupted and the family faced an unimaginable challenge. Emily, a devoted homemaker for her entire life, was thrust into a new role, one that required her to provide and protect her beloved children. She sold their cherished family home at Aboo Sittee Lane and moved to a smaller house at 253E in Kampung Sireh (located along Lengkok Burma, Codrington Avenue and Burma Road). The huge pieces of land her late husband Louis Sr. had acquired in Peel Avenue, where the Island Hospital now stands, were sold to ensure their survival through the Japanese occupation in Malaya.

In the wee hours of the morning on 9 December, air raid sirens wailed, a haunting prelude to the impending tragedy. Eight Japanese planes machine-gunned the small air strip in Bayan Lepas, incapacitating the runaway. On the afternoon of 10 December, a one-sided dogfight over Mata Kuching aerodrome was seen with 26 planes taking part in this raid and not more than half a dozen RAF fighters went up to engage them. In two days, the Japanese easily decimated the Royal Air Force and the Royal Australian Air Force, securing total aerial supremacy. Emily, like a fragile leaf in a storm, learned that the Butterworth airbase and nearby oil tanks had also been set ablaze.

On 11 December, bombs were dropped on densely populated parts of Chinatown in Penang. The bombs that rained down included heavy demolition, light anti-personnel and incendiary devices, each one a harbinger of death. As recounted by the editor of The Straits Echo, Manicasothy Saravanamuttu, this relentless assault bore a grim toll, reducing “some 500 buildings were destroyed in George Town and 150 bodies were rotting on the streets”.

The British, infamously, looked after themselves first. By 14 December, most European women and children had evacuated and by 16 December, almost the entire European civilian population abruptly departed without warning.

The fear that enveloped Emily was like a thunderbolt, overwhelming her with the devastating reality. So much had already been lost that year and the spectre of further losses loomed ominously. It was in the darkness of those turbulent times that Emily’s heart whispered fervent prayers to the heavens, a plea to keep her eight children safe. “Tuan Allah, please protect them all”, she implored, as she bargained with the divine for the safety of her precious family.

Vintage kebayas with intricate embroidery, reminiscent of the exquisite embellishments that Emily would have been familiar with.

Amidst the wartime chaos, Emily's indomitable spirit, though brutally shaken, burned even brighter. The orphan, who had once learned to sew in the hushed corridors of the convent, now harnessed that skill to make ends meet, regardless of how meagre the earnings. Her beautiful embroidery, gracing kebayas with intricate floral masterpieces, served as a testament to her resilience and unwavering creativity in the face of daunting hardships. As her grandson penning this story, one of my deepest regrets is never having the chance to own one of her elegant creations. My Mum often noted their exquisite beauty, the living embodiment of Emily's strength and resourcefulness evident in every stitch.

In the haunting tapestry of war, as portrayed through Mum's eyes, beneath all lies a tale of unyielding courage and heartache, a narrative woven with threads of suffering. It is a story that, in its own way, evokes the poignant spirit of Studio Ghibli's "Grave of the Fireflies", for it is during wartime that childhood innocence is most brutally at lost, leaving scars that time alone cannot heal.

For the Martins, their daily existence was marked by frugality and scarcity. Emily cooked rice when possible, often diluted porridge or porridge with kacang hijau (mung beans). The family grew their own vegetables and fruits such as sweet potatoes, brinjal, long beans, winged beans, kangkung, bayam, murungai (drumsticks), jambu, papaya, banana, coconut and chillies. Yet, nature's bounty did not yield its treasures overnight; sweet potatoes, for instance, demanded patience as they matured over three to four long months. Meat was a rarity on their table, although they raised their own chickens and ducks. The ache of hunger was a constant companion, a relentless reminder of the scarcity that war had thrust upon them. Mum noted that they often ate most of the vegetables they grew as raw ulam with sambal.

Margaret, barely a teenager, bore the weight of wartime challenges with incredible resilience. She worked as a waitress during those dark days. Once, a kind-hearted Japanese soldier who took a liking to her, gifted her a huge gunny sack of rice, a lifeline in their sea of deprivation.

The war was a relentless storm that battered their lives. Mum recounted the fear and uncertainty of those times. It was an era when George Town teemed with Japanese soldiers, their presence a haunting reminder of the occupation. Yet, interactions with the occupying forces were kept to a minimum, a necessary measure to avoid trouble.

One harrowing day during curfew, Emily returned home from the market to a chilling sight. Japanese soldiers, invaders of her home, were ransacking everything. In the midst of the chaos, one soldier callously hurled a wooden chair in her direction, a perilous act of aggression. With God looking out for her, the chair fell short, sparing her petite frame, barely reaching five feet in height, from a potential fatal fate. With fear pulsing through her veins, she fled the perilous scene as swiftly as her nimble feet could carry her. The soldiers, it seemed, must have been searching for ammunition, firearms or any item they deemed valuable for their war effort. This terrifying intrusion into their lives, thankfully, proved to be a single event during the long and arduous years of the war.

Many households dug air raid shelters as they awaited the terrifying threat of bombings. These were times that echoed with the chilling memory of beheadings, as the Japanese military resorted to such brutal measures to maintain control. The family's unwavering faith and prayers became their sanctuary in the midst of the storm. Their belief in perseverance and resilience was the lighthouse that guided them through the darkest of nights.

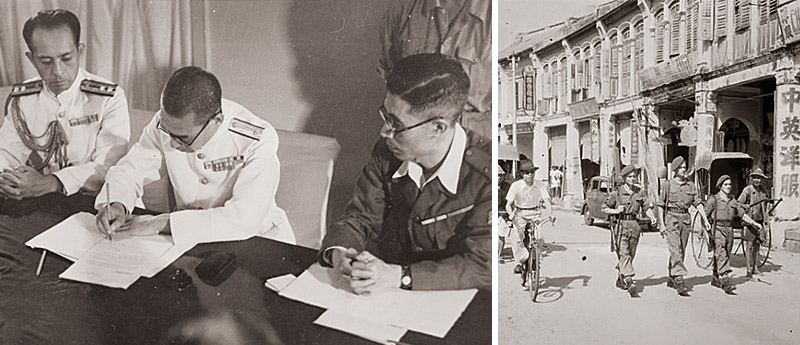

Left photo: 4 September 1945: Admiral Bazudi, commander of Japanese forces, Penang, signs the surrender document watched by the Japanese Lieutenant Governor of Penang (right) and the admiral’s chief of staff, Captain Hidaka. Photo: Public Domain.

Right photo: September 1945: Three members of the RAF Regt on foot petrol in George Town, Penang. Photo © Imperial War Museums

September 1945: British forces drives through Penang after the Japanese surrender. Photo: Public Domain.

As this story unfurled amidst the tempestuous backdrop of war, it became a tapestry of unwavering love, indomitable strength and the enduring spirit of a family bound not only by blood but also by adversity. Emily, with her skill in floral embroidery, embodied the quintessential Nyonya characteristics of frugality, resourcefulness and an unwavering ability to make the most of her surroundings. These enduring traits resonate in her family’s heart, a testament to love’s guiding light that continues to inspire, a legacy echoing in Mum and hopefully, in me as well.

Baby Yolanda with her parents Margaret and Mac, and her sister Esther. The beautiful christening gown was sewn by Emily. Photo © Yolanda MacFarlaine

Emily and her grandson, Adrian Cheah, with Emily donning a kebaya paired with a batik sarong. Her hair elegantly coiled in a bun. Emily lived a full life, reaching the age of 84, leaving behind a legacy of love, resilience and an enduring spirit.

Written by Adrian Cheah, grandson of Emily Elizabeth Surin

© All right reserved

9 November 2023

The story was first published in Nov 2023 in the 103rd State Chinese (Penang) Association Celebratory Souvenir Programme.