The intriguing tale of deliverance behind the Hokkien New Year

The ninth day of the first lunar month holds deep significance for the Hokkien people, a subgroup of the Chinese community. Some traditionalists even regard it as more important than the first day of Chinese New Year, as it marks the day their ancestors were spared from massacre. According to legend, the Jade Emperor, also known as the God of Heaven, provided them with divine protection. As a result, Hokkien communities – especially in Penang – observe this occasion with even greater reverence and festivity.

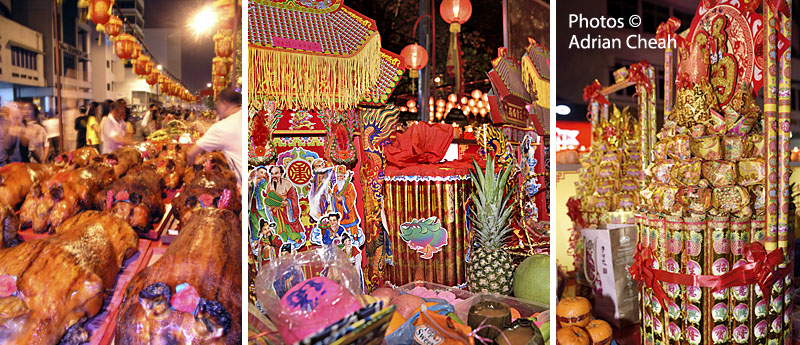

If you are in Penang on the eve of the celebrations, head to the clan jetties in the heart of George Town. There, you will witness the festivities in full swing and a grand offering table laden with an array of traditional delicacies prepared for the God of Heaven.

There are several versions of the Hokkien Pai Ti Kong (praying to the God of Heaven) story. One of the most well-known traces its origins to the 16th century, during the Ming Dynasty. At the time, oceanic trade was thriving, with cargo ships frequently sailing to major ports. This prosperity, however, also attracted bands of pirates who roamed the seas in search of plunder, particularly along China's eastern coastline. According to this account, a fateful event unfolded on the first day of Chinese New Year when a group of ruthless pirates descended upon a Hokkien village in Fujian Province. Attacking from all sides, they mercilessly rampaged through the village, leaving no one spared in their path.

Fearing for their lives, the villagers fled into a nearby sugarcane plantation, praying to the God of Heaven for deliverance. Despite days of relentless pursuit, the intruders failed to find them, as the tall stalks provided effective concealment. On the ninth day of Chinese New Year, the pirates finally abandoned their search and left the village.

In gratitude, the Hokkiens emerged from hiding and offered prayers of thanks to the God of Heaven for their survival. From that moment, they vowed to commemorate their deliverance with grandeur, offerings and prayers, giving rise to the annual celebration on the ninth day of the first lunar month – a day they could truly embrace their renewed lease on life. However, prayers and offerings to Thee Kong had been observed long before this event, with the ethnocide only deepening its significance for the Hokkien people.

According to the lunar calendar, a new day begins at 11:00 pm. As such, Hokkiens typically start their prayers at this hour on the eighth day, though preparations for the auspicious occasion begin well in advance.

Preparations for the festivities begin on the morning of the eighth day, as Hokkiens head to the market procuring essential items integral to the celebration. These include fresh sugarcane stalks, a whole roasted pig for those who can afford it, cooked meats, Ti Kuih (sweet sticky rice cakes), Ang Koo (red tortoise cakes), Mee Koo (bright magenta-coloured buns), Huat Kuih (steamed rice flour cupcakes that rise and “bloom”), Bee Koh (glutinous rice pudding), miniature pink sugared pagodas, fresh fruits and fresh flowers. Each of these items bears symbolic significance, epitomising abundance and auspicious fortune, making them indispensable components of the celebration.

During this time of year, long stalks of sugarcane are a common sight across Penang, especially in bustling market areas. It is fascinating to see how people transport them – some extending out of car windows, others carefully balanced on motorcycles, showcasing remarkable ingenuity in handling these long stalks.

On this auspicious night, the Hokkiens express their gratitude by preparing a meticulously decorated offerig table filled with offerings that symbolise prosperity. A customary practice involves affixing a pair of lengthy sugarcane stalks to the sides of the offering altar or table. They symbolise unity and harmony as well as cooperation and strength. Together, they are a token of anticipation for fruitful and "sweet" outcomes.

Certain festive fruits are also placed on the offering table, often decorated with red paper cuttings bearing auspicious Chinese characters. Cuttings of red "pineapple flowers” are a common sight, symbolising prosperity and good fortune. Everything is well curated and nothing is left to chance.

The pineapple, or "ong lai" in Hokkien, is a key offering during the Hokkien New Year, as its name sounds like "prosperity comes". Often decorated with red paper cuttings, the pineapple is placed prominently on the altar to invoke abundance. Kim Chua pineapples, crafted from sheets of gold paper and folded origami-style to resemble a pineapple, are readily available throughout Penang during the season. For those unable to create them themselves, these decorative pineapples can easily be purchased.

Hokkien businessmen take the festival quite seriously. Their lavish and generous offerings, some of which are votive in nature, are seen as a reflection of their hopes for prosperity in the year ahead. As a result, they spare no effort, going all out to celebrate with abundance.

Integral to this celebration are the meticulously folded piles of "gold paper", colloquially known as Kim Chua, fashioned into the shapes of ancient ingots. They are set ablaze in a bonfire, constituting a thanksgiving offering to the Jade Emperor. As the gold "ingots" burn, family members would add the sugarcane stalks from the altars into the towering flames, adding to the symbolic ritual.

Thundering firecrackers and fireworks light up the night to mark the beginning of the ninth day of Chinese New Year, celebrating the joyous deliverance of the Hokkiens. It is also believed that the loud explosions help drive away evil spirits, setting the stage for a year of peace and prosperity.

---------------------------------------------------------

Written and photographed by Adrian Cheah

© All rights reserved.

Updated 2 February 2020

PS: Several of the photographs accompanying this story capture poignant moments from the annual celebrations held at the home of a dear friend. It was a cherished tradition where some of my closest friends and I would gather to revel in the festivities of the Hokkien New Year. Sadly, Lee Lock Soon passed away in March 2023. For years, I had the privilege of celebrating this special time at his home, where his warmth, kindness, and laughter made every moment unforgettable. To my dearest Lock Soon, your absence is deeply felt, and your memory remains forever in our hearts, cherished with fondness and love.