Penang's Cina Wayang (Chinese opera) – for gods and ghosts

Growing up in Ayer Itam in the 1970s was like living in an endless festival. The wet market was our food playground, where you could buy something delicious at any time of the day. We would show up with our own tiffin carriers and even supply our own eggs to the char koay kak lady or Pak Dollah, the mee goreng uncle, who always accepted them without batting an eyelid. Ah Heng, the rojak man, parked his cart in front of my house. He would skewer halved green mangoes with a lidi (coconut leaf stick), smothering them in thick rojak sauce and crushed peanuts, creating a truly scrumptious snack. His sliced bangkwang, topped with similar ingredients, was another of my favourite treats. When Ah Heng eventually pivoted from rojak to koay teow th'ng, it was a welcomed change. His bowl of noodles was packed with minced pork, pork slices, liver, fish balls and topped with bak yu phok (fried lard) and spring onions.

In those days, everyone knew everyone, and gossip travelled faster than a bullet train. By the time I walked home, my mum already had a full report of my escapades.

Nowadays, Chinese opera shows are few and far between, mostly appearing during the Hungry Ghost Festival or a deity’s birthday. But back in the 1970s and 1980s, they were a regular spectacle and the atmosphere was electric – like stepping into a carnival. Food stalls and petty traders lined the area, transforming it into a kid’s paradise. Picture this – you could try your luck at “tikam", paying to select a ticket for a chance at a mystery prize. You could enjoy “ice cream potong” sandwiched between two wafer biscuits or spin a wheel to win a water pistol. The mouth-watering scent of freshly grilled roti bak kwa and cuttlefish wafted through the air, tantalising your taste buds.

The crowd was huge, with people bringing their own stools to snag the best view of the classic Teochew opera stories. The drama on stage rivalled the excitement in the audience as everyone jostled around the stalls while being entertained by the dramatic live performance. It was a riot of sights, sounds and flavours – a chaotic celebration that left a lasting impression on anyone lucky enough to be part of it.

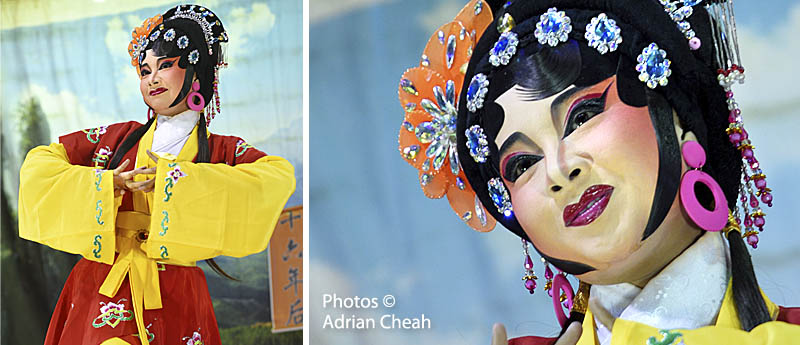

My brothers, sisters and I needed only to cross one road right in front of our house and stroll down a narrow alley to reach the open area where the performances took place. I was captivated by the extravagant costumes embellished with auspicious creatures like dragons and phoenixes, shimmering headdresses and the dramatic music that filled the air. We sat there, glued to our seats, as the performers whisked us away into a whirlwind of murder, sword fights and romance. Each of them, dolled up with heavy make-up, delivered the performance of their lives.

Every change of scenery was pulled off with a pulley system that revealed floor-to-ceiling hand-painted backdrops, transforming the stage from a battlefield to a tranquil courtyard in an instant. It was like watching a live-action soap opera, where the stakes were high and the characters were larger than life.

A small band of musicians, partially concealed at the wings of the makeshift stage, provided the theatrical soundtrack for the opera. Traditional musical instruments like the gaohu, erhu, yehu, pipa, dizi, gongs and cymbals created the distinctive sound of Chinese opera. The stage itself shone like a beacon in the darkness, illuminated by fluorescent tubes and spotlights, casting an enchanting glow over the unfolding drama.

Ironically, I fell in love with Chinese opera, even though I could not understand a single word the performers were saying. I did my best to interpret each story through their facial expressions and gestures. The male characters, with their long beards, emitted deep, growling tones, while the female characters sang in high-pitched, melodic tunes. Some wore white silk extensions attached to the sleeves of their garments, which amplified their emotions as they flung their hands. For example in moments of despair, the heroine would dramatically throw her hand up in the air, only to collapse to the ground in anguish.

I practiced this at home, tying my father's white handkerchiefs to my wrists and imitating their gestures. To me, it was like poetry in motion, but my parents would have none of it. They considered it silly and would brandish the cane, putting an end to my operatic aspirations.

Revisiting Chinese opera in 2019, I armed myself with a camera to document its world on the open grounds near Universiti Sains Malaysia along Jalan Bukit Gambir. To my surprise, aside from three other photographers, there was only one audience member – a solitary elderly man! Can you believe it? Just one person! Gone are the days when these performances would draw in the local community, offering a chance to gossip and strengthen bonds over the excitement of live shows. Nowadays, people seem more interested in their Netflix marathons, comfortably cocooned at home. Thank goodness the gods and ghosts were there to witness a brilliant performance, even as the living chose to turn their backs and stay away.

Arriving early, I had the chance to capture the dramatic transformation of the performers into either enchanting opera beauties or menacing villains. Exaggerated designs were meticulously painted on their faces, symbolising each character's personality, role, and destiny. Specific colours signified distinct attributes: a red face conveyed loyalty and bravery, black denoted courage, while white or yellow faces indicated duplicity, often representing the villain. Golden or silver faces added an air of mystery to the mix.

In addition to colour, lines also served as symbols. For instance, a face could be entirely painted white or focused around the nose; the larger the white area, the more diabolical the character's role. Witnessing the application of makeup was truly awe-inspiring. The skill and meticulous attention to detail were remarkable, with even small patches of wigs made from real hair carefully added to fringes and sideburns. When the transformation was complete, it was nothing short of resplendent.

This passionate opera troupe was from Thailand, and its members proved to be captivating subjects for photography. They lived in humble tents pitched within the temple grounds where their performances took place. Their warmth and strong sense of camaraderie were palpable. I observed and wholeheartedly appreciated their dedication to this fading art form and their tireless efforts to preserve it.

I felt privileged to witness the performance, but it was hard not to feel a twinge of disappointment at how little attention this traditional art form receives from the locals nowadays. It is a shame, really, because with all the grandeur surrounding Chinese festive occasions in Penang, you would think we would be turning out in numbers to support these performers. Still, I hold onto hope. With a little effort and some awareness, we might just spark a revival. After all, we need to rekindle appreciation for these timeless treasures and ensure they thrive for generations to come.

-------------------------------------

Written and photographed by Adrian Cheah

© All rights reserved

16 August 2019