The legend of the ferocious beast called Nian

In Mandarin, the word "Nian" translates to "year". Yet, according to legend, Nian was far more than a mere symbol of time's passage. It was a fearsome, mythical creature that struck terror into the hearts of people during the New Year, so menacing that it threatened the very existence of humanity. Nian is said to have roamed the land in ancient China, during a time known as shànggǔ (roughly translated as "a very long time ago").

Faced with the looming threat of destruction, the Emperor turned to his advisors for guidance on how to avert the impending calamity. After much deliberation, the advisors came up with a brilliant strategy. They approached Nian and challenged the fearsome beast to demonstrate its unmatched strength by destroying all the other monsters on earth, rather than targeting humans who posed no real challenge to its might.

Nian accepted the challenge and a year later, after triumphing over every other monster, it returned to the humans. Drunk on its newfound power, it revelled in the fact that nothing could stand in its way. Unfortunately, its desire to annihilate the entire human race remained as strong as ever.

At that moment, some children were playing with firecrackers. The deafening explosions startled Nian, causing it to retreat in fear. The humans, surprised by this unexpected reaction, erupted in celebration. The air was filled with a mixture of awe and relief – after all the terror, the beast had been vanquished by something as simple as noise. From that pivotal moment onwards, the tradition of using firecrackers during Lunar New Year celebrations has been upheld through generations. The belief remains that these explosive sounds serve to ward off malevolent creatures like Nian, ensuring safety and prosperity for the year ahead.

Another version of the legend tells of an immortal god disguised as an old man who confronted Nian and proposed the same challenge – to vanquish all other monsters before turning its attention to humans. After triumphantly defeating the other creatures, Nian returned to the old man.

“Old man, your time is up and I shall enjoy devouring you!” declared Nian with a satisfied smirk.

“Oh very well, but let me remove my clothing first. I should taste much better that way", the old man calmly replied.

As he began to disrobe, revealing his red undergarments, a wave of terror swept over the ferocious beast. Overwhelmed by its inexplicable fear of the colour red, Nian fled in panic, sparing the old man's life.

When the villagers emerged from their hiding places, the atmosphere of fear dissipated and peace returned to the community. The sense of relief was palpable, as the villagers slowly realised that they had been spared from the monstrous threat. Before leaving, the immortal revealed his true identity and offered the villagers a piece of invaluable advice. He instructed them to hang red paper decorations on their windows and doors at the end of each year. This, he explained, would capitalise on Nian’s fear of red, ensuring the safety of their homes and warding off the beast in the future.

The phrase "guò nián" (过年), which originally meant "survive the Nian", later evolved to mean "celebrate the year". In Mandarin, the word " guò" carries a dual meaning – "to pass over" and "to observe".

Interestingly, red underwear has become a fashionable choice within the Chinese community during the Lunar New Year. It is widely believed that wearing red underwear during this festive period attracts good fortune throughout the year. In Chinese culture, the colour red symbolises loyalty, success and happiness, making it a popular and auspicious choice for celebrations. For those who enjoy a bit of extra luck – say, in the form of a winning hand at the mahjong table or in a card game – red underwear might just be the secret weapon! After all, who does not want to feel lucky in more ways than one?

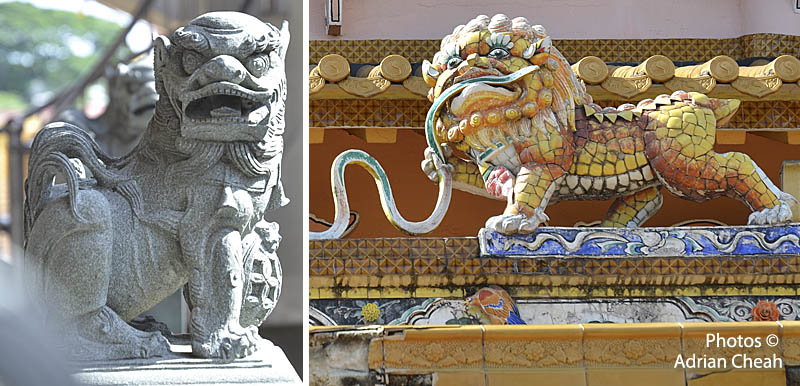

The lion was believed to be the only animal capable of harming the ferocious Nian. Some say this belief gave rise to the lion dance, where villagers, inspired by the lion’s supposed strength, endeavoured to replicate its movements in a collective effort to intimidate and drive away the fearsome beast. The lion’s image has long been associated with strength, courage and protection in Chinese culture. In fact, the lion is commonly regarded as a guardian at temple entrances, kongsis and grand homes, believed to ward off evil spirits and usher in good fortune.

In Penang, lion dance troupes are an integral part of the 15-day Chinese New Year celebration. Their role is to drive away evil spirits and bring good fortune to various places, including private homes, business premises, hotels and shopping complexes. Performers demonstrate incredible feats of balance, standing on one another’s shoulders to retrieve an ang pow (a red packet containing money) securely fastened to the top of a tall pole. These performances, which often take place in front of crowds eagerly awaiting good luck, are a reminder of the continuing tradition that links the mythical past with present-day practices.

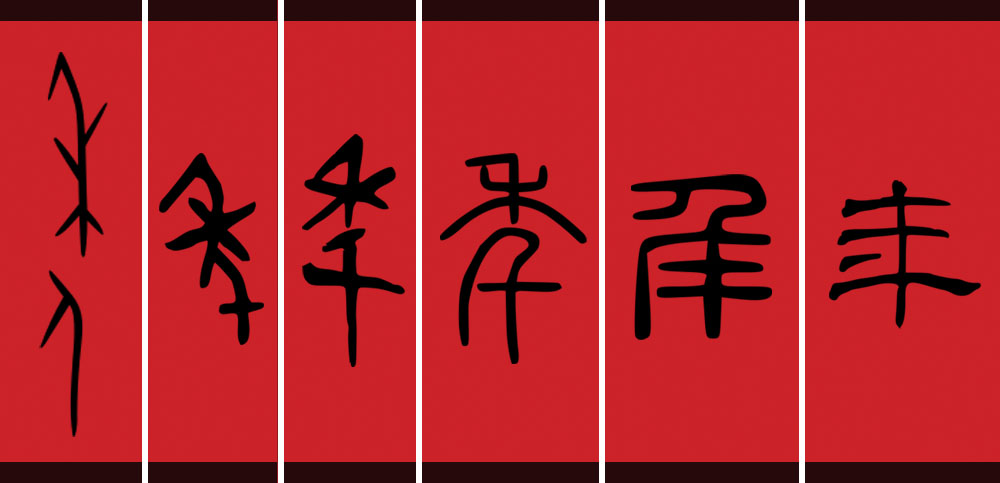

From left, the evolution of the character 年 in the: oracle script, Spring and Autumn bronze script, Qin slip script, Shuowen seal script, Shuowen ancient script and Clerical/scribal Qing script (public domain).

The habits of the mythical beast Nian are elusive. While the creature plays a central role in the folklore surrounding Chinese New Year, no ancient written records or official folk customs explicitly reference it. The earliest forms of the character 年 (nián), meaning "year", appear in oracle bones – the oldest form of Chinese writing – depicting a person carrying a stalk of ripened grain, symbolising the harvest. Over time, this character evolved and by the second century, it was written as 秊 (nián), meaning "the ripening of grain". These early records focus on agricultural cycles rather than any mention of a mythical monster.

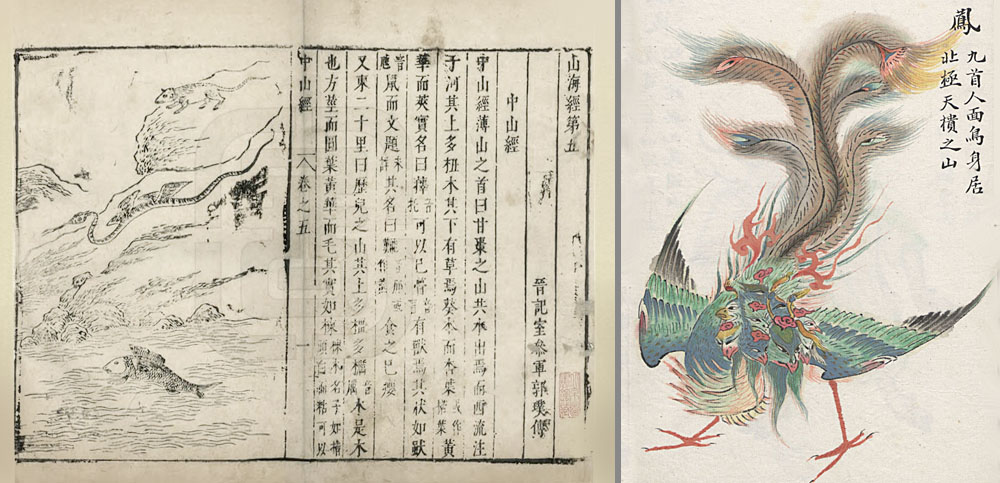

Left: Scroll pages from volume five of the Classic of Mountains and Seas, a woodblock-printed edition from the Ming dynasty (1368–1644).

Right: Illustration of a nine-headed phoenix from the Classic of Mountains and Seas, colored version from the Qing dynasty. (public domain)

Furthermore, the Shan Hai Jing (Classic of Mountains and Seas), a well-known ancient text cataloguing mythological creatures and natural wonders, makes no reference to Nian. This absence from such an established compilation suggests that the legend of Nian and the customs surrounding it, may have evolved independently of the recorded mythological traditions of early China.

That said, the legend of Nian has given birth to numerous customs still observed during the Spring Festival today – firecrackers, the lion dance and the use of the colour red! Like every great legend, the story of Nian carries a deeper message. It is not just about a fearsome beast but a reminder that challenges can be met with creativity and unity. The villagers, using firecrackers and the colour red, demonstrated that resourcefulness and collective spirit often triumph over brute strength. These traditions remind us that it is our ingenuity and togetherness that protect us, ensuring safety and prosperity.

---------------------------------------------------------

Written and photographed by Adrian Cheah

© All rights reserved

10 February 2018