Madam Hong and Cheng Beng

There are some who believe that traditionally, the task of performing Cheng Beng rituals falls on the family of the eldest son, followed by the next in seniority and so on. The eldest son is thus entirely responsible in ensuring that the rituals of ancestral offerings are carried out properly.

Madam Hong's mother passed away in 2006 after a long illness. Being a new convert to the Roman Catholic faith, Hong was understandably hesitant initially to perform Cheng Beng rites for her mother. She was torn between filial piety and being a good Christian. After some soul searching, she realised that the rituals of Cheng Beng could be carried out in such a way as not to transgress her Christian values. She promptly went ahead and performed the necessary rituals.

According to the late Father Peter Shyu of the Holy Name of Jesus church in Balik Pulau, Christians wishing to honour departed relatives of other faiths may do so. He said that what mattered was a person's intentions because that alone distinguished between holding a joss stick in prayer and holding one as a mark of respect for the dead. While the former is forbidden for Christians, the latter is acceptable.

Today, the ashes of Madam Hong's mother are sealed in a niche in the Batu Gantong columbarium. Although the cost was steep (RM3,200) the convenience of not having to worry about keeping a grave clean was well worth it.

Madam Hong's ancestral tablets have also found a permanent home at the Chin clan house in Penang. Prayers are conducted here by the Chin clan for their ancestors during the Feast of the Hungry Ghosts in August and the Winter Solstice in December, so living descendants needn't have to worry about their ancestors being neglected. The cost of having ancestral tablets housed in clan associations are reasonable - RM500 plus ang pow for the mediums.

The very first Cheng Beng

How did the practice of Cheng Beng originate? Legend has it that a man by the name of Jie Zi Dui who saved his starving general's life by serving him with a piece of flesh cut from his own leg. To repay Jie's selfless deed, the general invited Jie to rule over a principality with him. Jie however declined, preferring to lead a quiet life with his mother in the mountains.

Thinking he could get Jie to change his mind, the general set fire to the mountains. The tactic failed and Jie was burnt to death. Overcome with remorse, the General ordered all fires to be put out on Jie's death anniversary. Thus began the custom of preparing food without fire, otherwise known as cold food, and since that day, a 'cold food' festival takes place on the eve of Qing Ming and is considered part of the festival.

Other accounts attribute the event to Emperor Shi Huangdi. Because it coincided with springtime, the Emperor would plant trees on the palace grounds to celebrate the renewing nature of spring. With the passing of the Emperor, this celebration of life became a day to honour him and the ancestors.

The origin of hell money

There is an interesting yarn behind the burning of hell money. One day a long, long time ago an old man from the "other side" helped a little boy called Wang Bo to win a writing competition.

In exchange, the boy had to help the old man settle a gambling debt of $10,000 with a spirit called Chang Lu. Elated with his triumph after the competition, Wang Bo completely forgot his promise.

When a flock of crows blocked his path, Wang Bo remembered the old man's request and immediately burnt mock money and joss paper at a temple dedicated to Chang Lu.

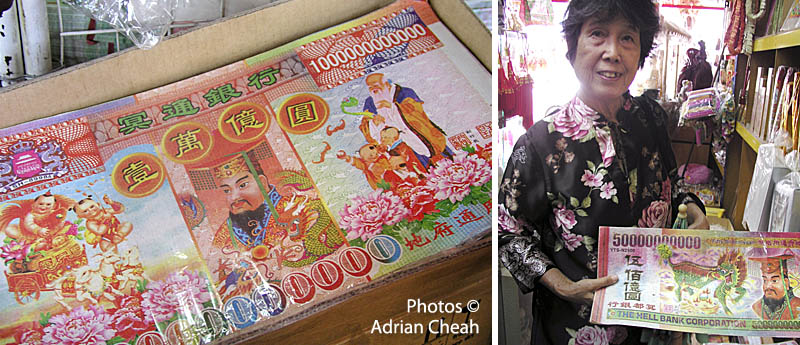

Since that day, the Chinese have been 'sending' money 'minted' by the Ming Tong Bank or the hell bank in huge denominations to the departed.

------------------------------------

Written by Raja Abdul Razak. Photographed by Adrian Cheah

© All rights reserved.

30 March 2006